How to acquire Worldly Wisdom instead of Expert Idiocy

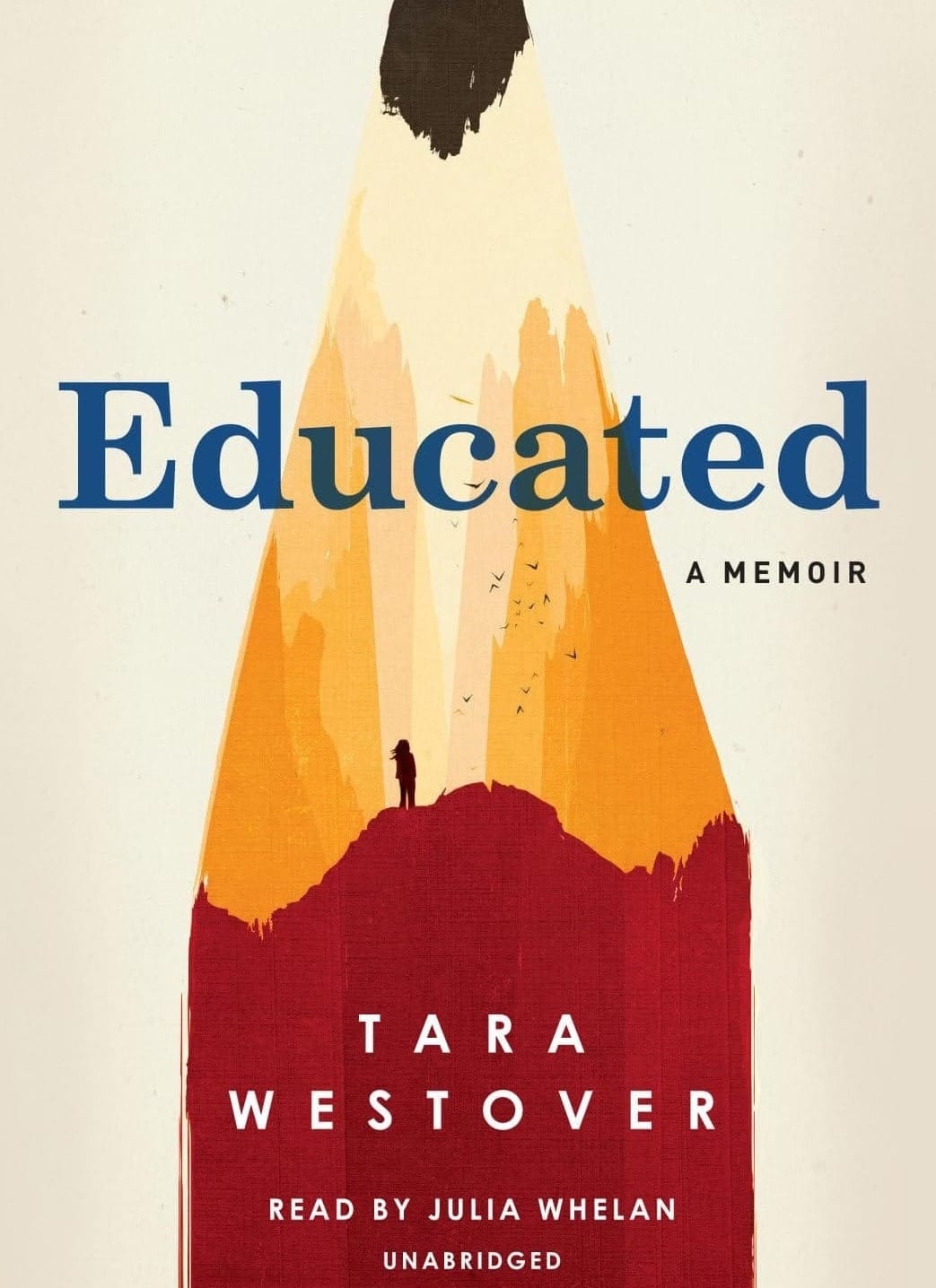

There is not a lot of buzz happening in the mountains of Idaho. Since this is where Tara Westover grew up, she spent most of her spare time playing in her father's scrapyard. And spare time she had. None of her siblings, neither herself, went to school. Being raised in a fundamentalist Mormon family, her father disliked the idea of the illuminati corrupted federal government influencing them. They did not have a birth certificate either, nor a medical record. Instead, they prepared for the end of times. Hoarding canned food and manufacturing their own rifle ammunition from scrap metal.

This small world made total sense for Tara. Indeed, her family not being alike was a source of profound pride. They were right, while the rest didn't get it. This world only got torn down, once she somehow managed to pass the ACT—the college entrance exam in the US. Watching her mother blossom after receiving education to become a midwife stirred a hunger within her—a yearning for the ominous world beyond the mountains.

First, she struggled to belong. The music her college peers cherished was foreign, their clothes unfamiliar. Not knowing any history or pop culture, she yet felt alienated. But as her universe expanded, the smallness of her family's world—their confining beliefs and her brothers' abuse—became the place where she could no longer belong.

Or such is the story of Tara Westover’s memoir “Educated” without giving away too much–in case you still want to read the book yourself. As I read it during my A-levels in school, it changed my perspective on education. This is what learning should feel like. World-expanding.

Yet, only seldom do we feel about learning new things this way. It's because we are learning about stuff, that we are not interested in. Perhaps we are not interested because they don't seem to effect our life in a positive way. They are not effecting us positively because the way we learn about those things, not allow us to utilize the information. The information we acquire is isolated instead of interconnected. This leaves us living just like we did before.

I am therefore looking forward to introducing to you a concept allowing us to think about the world from new perspectives, by learning about things that we are interested in, while doing so without memorisation.

Mental Models

It's the concept of mental models. Mental models are just like a map of reality. They are a simplification. Usually, an oversimplification and therefore not 100% correct. Still, they are useful. They allow us to orientate within the world.

The real test of knowledge is not whether it is true but whether it empowers us. Scientists usually assume that no theory is 100% correct. Truth, consequently, is a poor test for knowledge. The real test is utility.

– Francis Bacon.

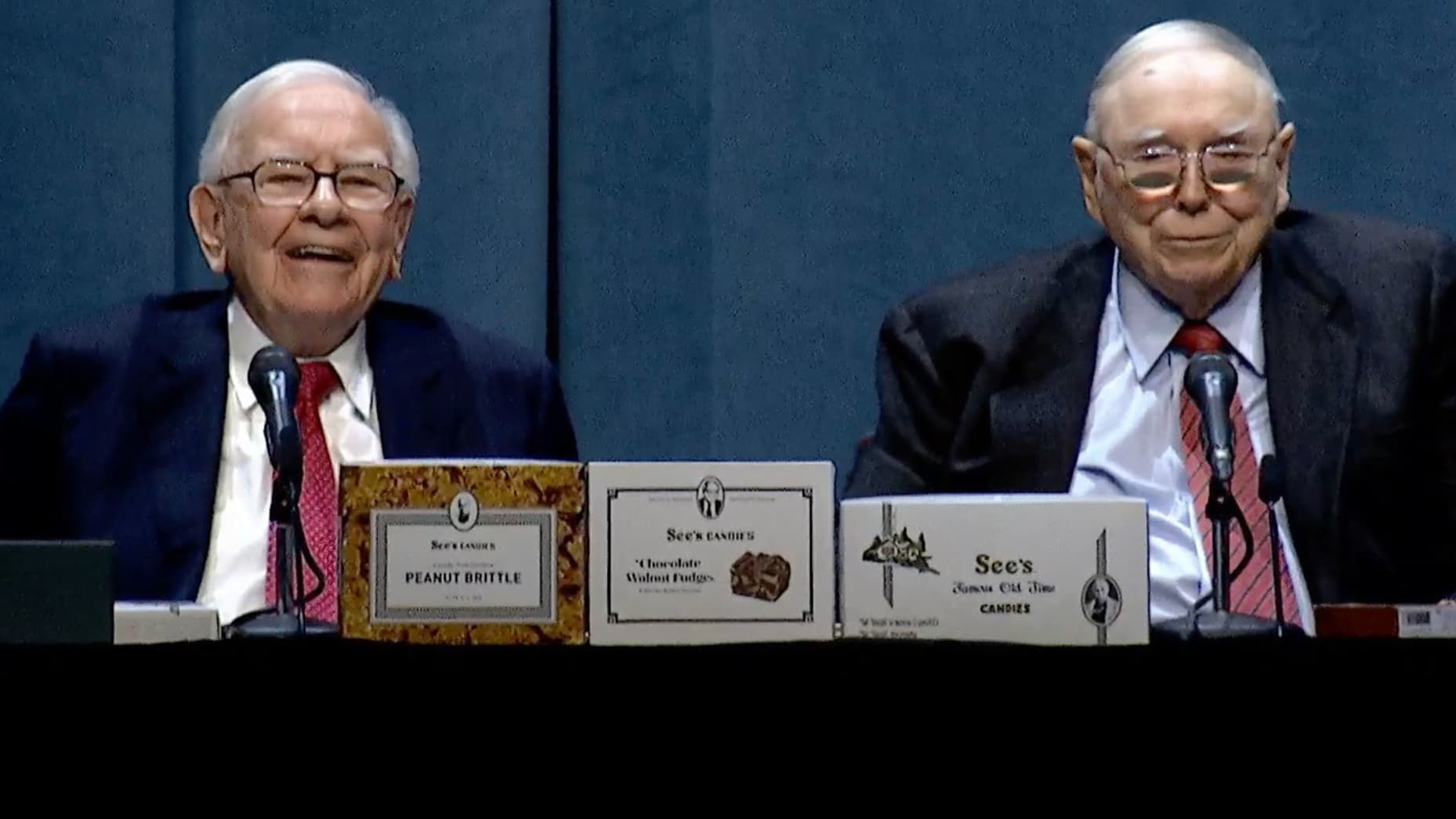

The concept of mental models was made infamous by Charles Munger. Together with Warren Buffett, he was the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway—one of the largest companies in the world, worth more than 980 Billion dollars.

He was praised for his 'wordly wisdom' and exceptional decision-making—before he passed away at the age of 99 in 2023. He himself contributed a lot of his success to cultivating a library of those mental models. They work like patterns of reality.

Invert, always invert!

One of his mental models, for instance, was “Invert, always invert”. Many things in life are better achieved by reverse engineering. Instead of asking yourself “What are all the boxes I need to check to succeed”, you would ask yourself “What are the things that could cause me to fail”. He would argue that you can get really far in life without making a lot of exceptionally well decisions, by just avoiding a few big mistakes.

To give an example more tangible: If you want to prepare for an exam, you would not go about it by learning the lectures one after each other, trying to obtain all the nice-to-know facts. Instead, you would start by identifying the few topics and questions that would unquestionably cause you to fail, if you don't know about them. From there, you then can expand your knowledge and learn about details.

Potentiality

Most things in life are not developing in a linear fashion. In finance, there is compound interest. If you earn 5% yearly interest on €100 over the cause of let's say 30 years, this 5% interest will start at €5 (€105 total) after the first year but end up at €20.58 (€432.19 total) after year 30.

The same is true for many other things in life. Learning works somehow exponentially too. We can remember things better by chunking them together (like sorting them in one category of information). The more we learn, the more adequate the concepts and categories that we can use to chunk new information. If you already learned about the French Revolution, you will have an easier time learning about the history of other revolutions. Or learn cello faster if you already learned the violin.

This mental model is especially useful because understanding this, you realise that there are only a few things that will change your life if you do them once but many things that are really impactful if you continue doing them.

Psychological Biases

For a long time, we believed that the human being is solely rational in his or her decision-making. The truth is, for plenty of decisions, that we claim are rational, we come up with rational reasons for them only after we already made the decision. Now, that's not groundbreaking news, still it is remarkable realising, to which extent this happens, once you learn about common biases in human decision-making. It probably pays off to learn about the most common flaws in human decision-making. Examples are: the self-confirmation bias, the sunk cost fallacy, the availability heuristic, the mere exposure effect and many more—with some of them being really bizarre.

How to come up with your own mental models

The great thing about mental models is, we only need to be somehow intentional about them in order for them to change our life. We can learn about any topic and just try to think of an abstraction for a rule that applies within this field of expertise, so that this expert knowledge becomes applicable in other pars of life.

I tried to create these abstractions with all of my articles yet:

- Ikigai (Japanese Philosophy) — Start imperfect to eventually become good.

- Inertia (Newtonian mechanics) — Keeping momentum is easier than building it up again (so be consistent).

- Habits (Operant Conditioning) — A tool for consistent behaviour. Initially requires conscious effort. Consists of a cue, a routine, and a reward.

- Failure (Biographies) — Feedback about reality. Not the opposite of success, but a necessary process on the way of getting there.

- Entropie (Thermodynamics) — If we want our life to be 'in order', we have the obligation to care for this order. Only chaos happens by itself.

- Antifragility (Risk Management) — To gain from chaos and uncertainty, don't spare yourself (unless the risk is existential) but make room for overcompensation.

To come up with your own mental models, just ask yourself when learning about a specific topic: “How can I apply this in a more general way? How does this apply to life itself?”

Of course, you can also understand and implement mental models created by other people. For numerous examples of mental models, you can read this article by Farnam Street. I am planning to curate and develop a lot more mental models for this newsletter. If you have not subscribed yet, do so, to not miss out on new articles. It's free!

If you liked the article, please share it with a friend or family member who is not aware of this newsletter yet! You can also share it on social media. I will be present there too soon. Until next Sunday!