How to start investing

»In Deutschland ist die höchste Form der Anerkennung der Neid« – Arthur Schopenhauer

Maybe for this reason, in Germany, investing remains a controversial topic.

Not talking about money related topics more openly, in my opinion, can only contribute to more inequality.

Against common beliefs, investing is not only for the rich.

Newer developments like Neobroker and Index-Investing are lowering the hurdles to get started and do well.

And there are excellent reasons to invest, especially if you don’t consider yourself wealthy. One prominent one is the failure of the German pension system (dt. Rentensystem).

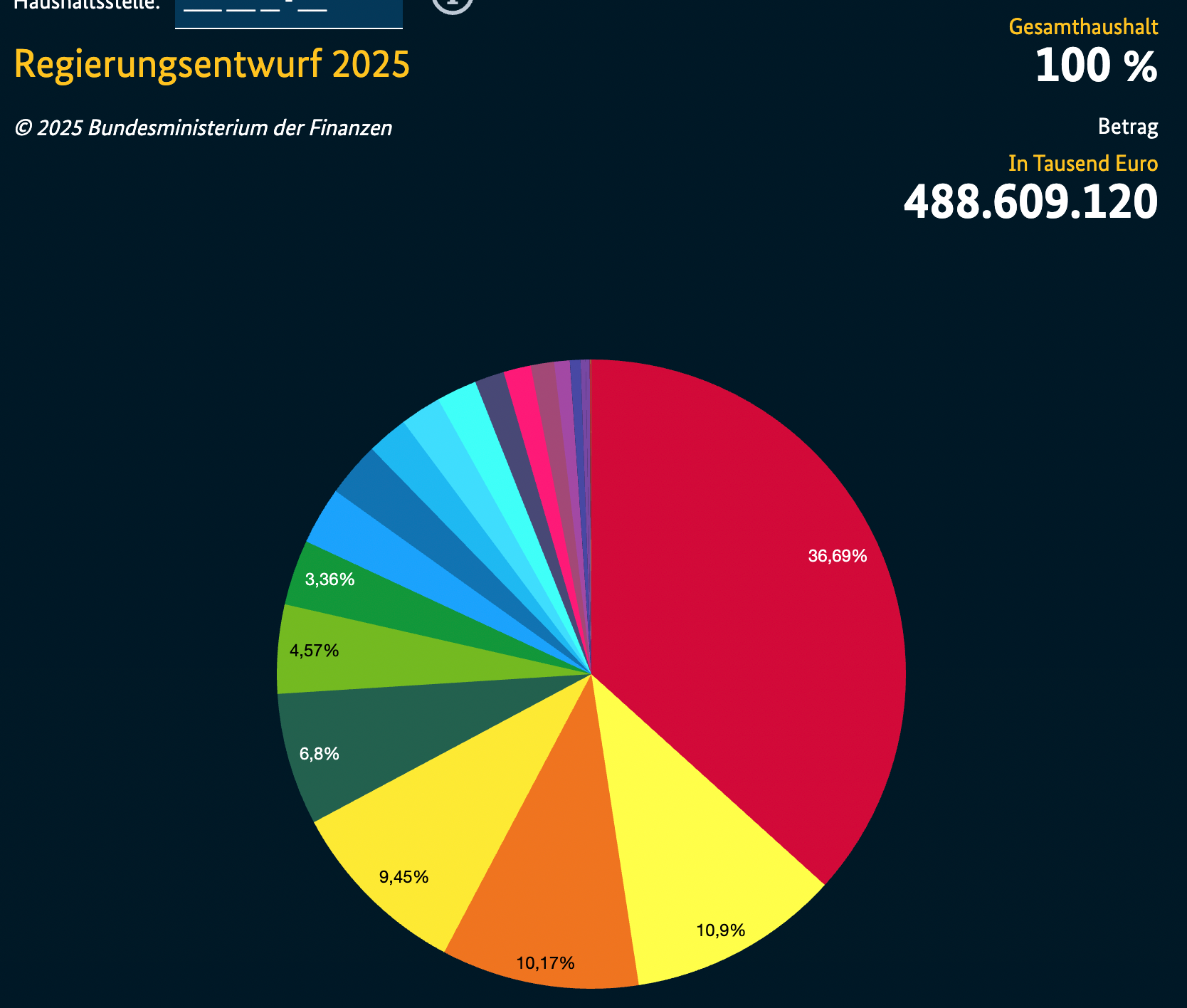

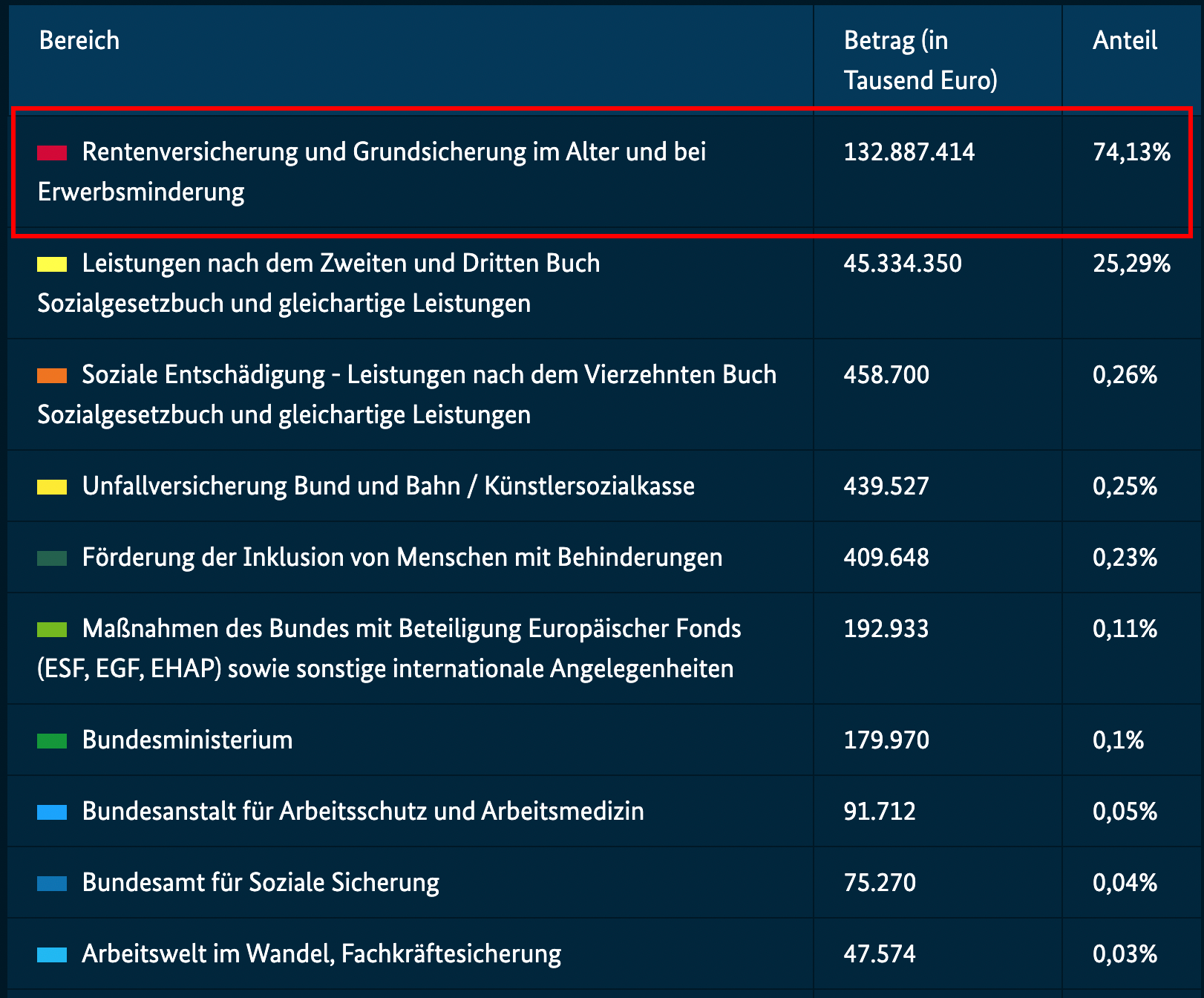

Here you see the draft for the “Bundeshaushalt” in Germany [1]. In total, 489 Billion Euros. In red, you see expenses for the “Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs” using around 37% of all tax money.

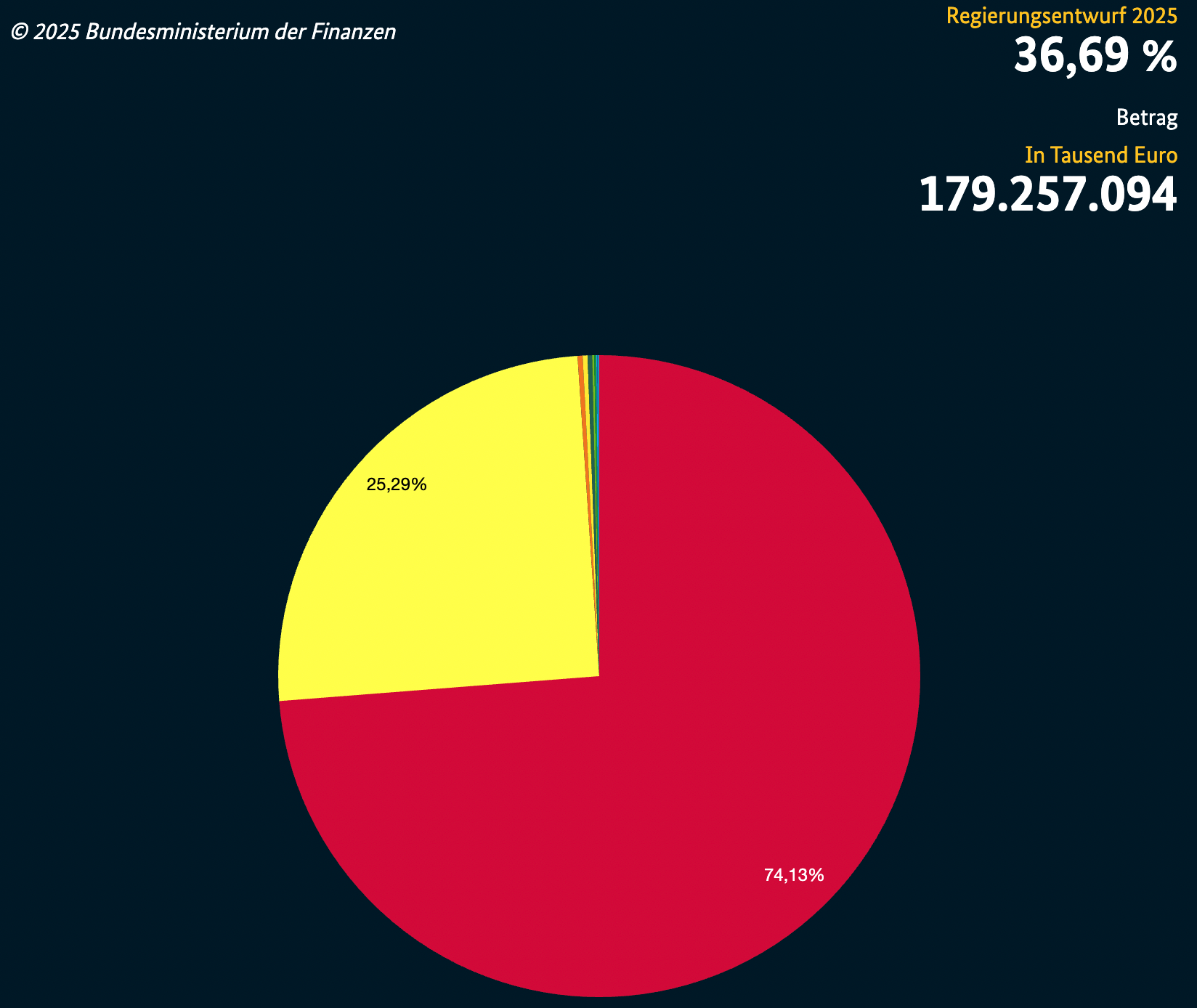

A closer look reveals that the majority of those costs are spent on “Pension insurance and basic income support in old age and in the event of reduced earning capacity”. The biggest part –again in red– is the “Rentensystem”.

133 Billion is spent here. That's 27%, almost one third of the overall budget. Please be aware that these are not the pension contributions you are already paying. These are subsidies to keep the pension system running.

In one of my recent articles “Factfulness” I wrote you should not just project a current trend into the future and assume the pattern remains unchanged. To practice what I preach, let's have a closer look.

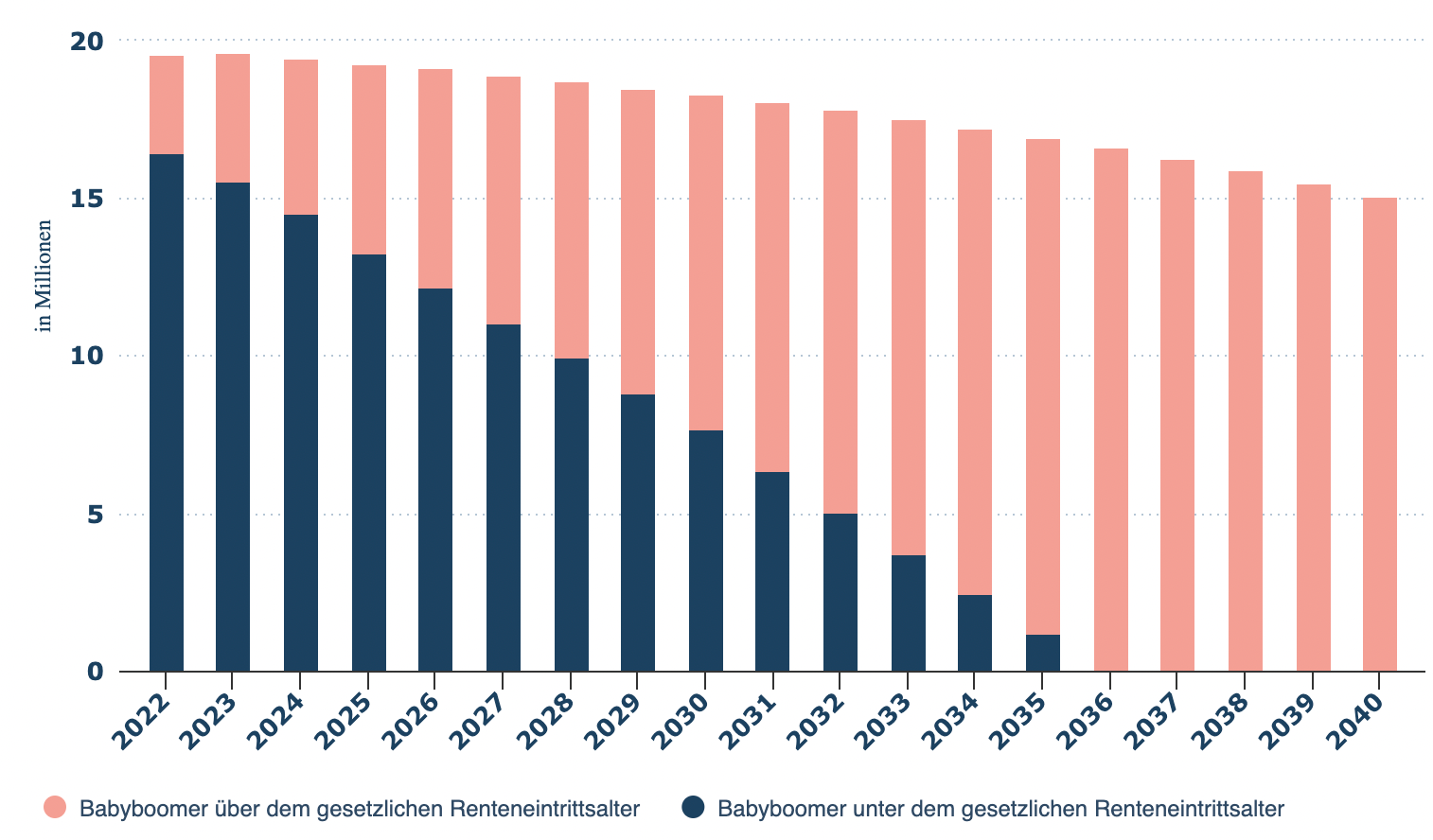

In fact, the particularly high birth rate generations, the “baby boomers” in Germany according to “das Deutsche Institut der Wirtschaft” (IW) are only entering the pension system since 2022 and will continue to do so until 2036 [2].

Based on this prediction, you can expect the current trend to get more pronounced during the upcoming years.

Demographic changes like ageing of the society are among the most predictable changes –since you know the number of people born in a specific cohort and that each year they will age one year… Thus, the prediction can be assumed to be accurate.

Why invest and not just save money

There is a substantial cost to saving money. You read that correctly.

- Cost that comes with inflation risk.

Inflation is a tricky concept because you don’t see it directly. The money in your deposit account is not getting less. Usually, it is getting more –though in the last years insignificant. But this money buys you less. This is also difficult to grasp because companies don’t want you to feel that their products get pricier. They’ll sometimes perform tricks like keeping the price but decreasing the package size.

Still, let's say in 2000 you put away €10.000. According to the German Federal Statistical Office [3] the purchasing power of that money 20 years later (2020) was equivalent to €7.552 (-24.48%). The real loss is lower because you would have received some returns on your deposit account. Still, you would have lost money because banks don’t give you the full EZB base rate as return. The return won't cover the loss of purchasing power.

- Opportunity Cost

This one is tricky too because again you don’t get to see it. It's the expense of missing returns on potentially invested money. For the MSCI World Index –an index commonly tracked by total market index funds– you’ll get an average yearly return of 9.5% over the last 20 years or 8.6% over the last 40 years [4].

If you calculate way more conservative with 5% yearly returns after inflation, during that same 20-year period this €10.000 would have turned into €27.126. That's due to compound interest. Over the time, you receive returns on your returns, making this effect more powerful, the longer you can keep the money invested.

If you want to play around with it, you can use this compound interest calculator.

In summary, saving money is costly. You should only save money if you cannot afford to invest it. To get an Idea of when you can afford to invest your money and when you can’t, let's have a look at the risks that come with investing.

Investment Risks

First, if you invest in single stocks, that is you buy shares of a specific company, there is business risk. The risk, that the company you bought shares of goes out of business. This would mean a total loss.

You can mitigate this risk by diversifying your investments. If you own shares of multiple companies and one files for bankruptcy, you lose less than if you’d spend all on that one company.

One common way to mitigate that risk is by investing in ETF's (exchange-traded funds). More about that later.

Second, another risk you face investing –even investing in an ETF– is the risk that comes with volatility. The price for which you can sell your shares of companies fluctuates. If you are forced to sell the shares when the price is low, you make less money or even lose money.

With volatility also comes the sequence of return risk. Even if two people get an average annual return on their investment of 5%, and are invested for the same number of years, their portfolio at the time of retirement can differ vastly.

The sequence of yearly returns matters. If the worth of shares you keep on buying goes down at the beginning of your investment journey, that's actually a good thing. You then get the new shares discounted, and they will eventually go up again–or so goes the logic of investing in ETF's. If you have those bad years at the end of your investment journey right before retirement, you don’t recover from that, which dramatically can harm your overall performance.

You can mitigate that risk by investing into less volatile investments the closer you are to your retirement. You'd also make sure to have an appropriate exit strategy.

However, for this reason, it is not possible to predict what your actual returns will be, even if the average yearly returns we saw historically would stay the same for the future –which is also not predictable.

For this reason, common advice is to not have money invested into stocks or funds consisting of stocks if your time horizon is less than 10 years.

Let's assume for now that you check this box.

How to get started

- Choose a broker and open a depot

To buy stocks, you first need a broker and a depot. This is where your shares are “stored”. For most people, it’s convenient to use a Neobroker. They offer lower costs, are more intuitive to use, and it's fast and easy to open a depot.

Just make sure the broker you use takes care of your capital gains tax. You can look at this comparison by Finazfluss to choose one. It's not too important which one you pick. It's more essential to decide one and get started.

I use Trade Republic, but I am sure others are just as good.

- Choose an investment

Here it's straightforward to give a general answer. Most people should not try to pick individual stocks. Most people should pick a low-cost total market index fund to get started with investing.

Let's dissect that.

- A total market index fund is a fund that consists of the biggest companies from different industries and different countries all over the world. The Idea is to not predict which companies will do better than others, but to reflect the overall economy, which historically grew around 8% per year.

- Look for an index fund that features multiple countries and multiple industries, i.e. that is well diversified.

- Look for a fund that is not actively managed. Actively managed funds (so-called hedge funds) usually underperform the general market. Index funds automatically track an index (which features companies based on their market capitalisation).

- Look for an index fund with low costs. Look for costs of lower than 0.3% p. a. of invested capital. The lower, the better. In comparison, hedge funds tend to cost around 2% p. a. which is a big difference. The higher the costs, the higher must be the returns to compensate for higher costs.

- You can choose between “accumulating” (dt. thesaurierend) or “distributing”. The first reinvests dividends automatically, which in Germany comes with a slight tax advantage. With the second, you get dividends paid out to you.

One ETF that suits all these criteria is a FTSE all World ETF.

To see more alternatives, you can watch this video by Finanzfluss:

- Set up an investment-plan for your ETF’s

Look up the budgeting part of my last article “Financial literacy” to figure out how much you can invest each month.

Even if it’s only €25 a month, I would strongly advise you start with that because this allows you to set yourself up for a crucial habit.

- Stick to your plan and don’t sell

A next important step is to display rational behaviour. This means not to sell out of panic if the market goes down or to sell, prematurely realising gains on your investment, if the market is up.

Although this is the shortest part of the article, avoiding irrational behaviour is the hardest part of all investing.

To get better, have a plan figured out that you commit to following. Keep learning about the topic. Just gain experience.

If you have a friend that could benefit from this article, share it. If you have not subscribed yet, consider doing so to get notified about new articles.

Until then!